This is the third installment of a four part series on testing. The next (and last) installment will be a testing resource list for EFL teachers.

How many tests have you created in the past academic year for your classes? Looking back at our teaching diaries for the period of time between April, 1996 and February, 1997, we were amazed to learn that between us we had designed, or had contributed to 12 tests. Regardless of your teaching situation, you'll probably be called upon to make similar numbers of official assessments of your students' learning over a period of time. Conventionally, assessment of this kind relies on tests written by the teachers themselves. Thus, in addition to our teaching, planning, and coping with day to day educational events, we are expected to test our students, and to make their performances meaningful to the students themselves, and to the school administration, in the form of a letter grade.

Undoubtedly, many teachers are uncomfortable with this reality. Graves puts her finger right on it in writing, "teachers tend to avoid extensive evaluation because they feel inadequate to a task in what they consider is the domain of 'experts,' for which special training in systematic analysis is necessary" (1996, p. 32). However, with a good grasp on some testing basics, there is no reason why teachers can't develop tests that effectively reflect students' learning in classroom situations. In this third article in the testing series, classroom tests will be characterized as criterion referenced tests (CRTs), which are used to estimate learning achievement, and thus have a potentially dynamic relationship with students' learning. Then, a basic process for classroom test development will be outlined. To further illustrate this process, the development of fairly large scale tests in a first year university/junior college core English program will be detailed.

What are CRTs?

Criterion referenced tests (CRTs) are used, according to Brown (1996), to measure students' abilities against "well-defined and fairly specific objectives" (p. 2). Brown links the educational purposes of diagnosis and achievement to CRTs. This makes sense, when you consider that in the context of a course, teachers need to know what students know and what they don't know (diagnosis), and need to be able to comment in some way on students' learning over time (achievement). The purposes of placement or admissions are best served by norm referenced tests (NRTs), which will not be discussed here. See Gorsuch (1997) for a more complete explanation of the differences between CRTs and NRTs.

The key to understanding CRTs and their design is an understanding of the term criterion. For the purposes of this article, criterion will mean, in Brown's words (1996, p. 3) "the material that a student is supposed to learn in the course." In an EFL writing course for instance, one of your criteria might be students' ability to differentiate between different rhetorical patterns such as persuasive or narrative essays. This really depends on what objectives you have set for the class beforehand, which will be discussed below.

Classroom Test Development: A Process

In this section, we will outline the general process of developing sound classroom tests. First, formulate course goals and objectives. According to Graves (1996), goals "are the general statements of the overall, long-term purposes of the course" and objectives 'express the specific ways in which the goals will be achieved' (p. 17). One example of a goal might be "the purpose of this course is to help students develop their ability to converse in English with their home stay families in the U.S." What must be done now is to consider specifically what students need to be able to do in order to converse with their home stay families. One specific, teachable skill that comes to mind here is the use of clarification requests, such as What? or Please speak slowly or I can't hear you. One of many objectives that could (and should) be written from this is: "the student will be able to make appropriate use of verbal clarification requests at least once in a realistic home stay role play situation." There are three elements of this objective that should be noted: (a) a specific context is given in which the student is to demonstrate her or his mastery of the objective (in a realistic home stay situation); (b) a level of mastery is stated (at least once); and (c) a specific criterion is named (verbal clarification requests). Good objectives need to have all three elements. See Graves (1996, pp. 16-19) for an accessible, sensible discussion on types of possible objectives in second language education.

It should be noted here that writing goals, and especially objectives, is not easy, particularly when working in a committee situation where members are likely to have very different ideas about the content and scope of ideal objectives. What is most important is that goals and objectives are formulated and written down, with the intent of revising them after the course is over. Like good tests, good goals and objectives are reviewed and revised over time, and should change to meet the needs and experiences of the students and teachers.

Second, decide what kind of test best fits your goals, objectives, and your situation. Note that the example objective given above has the student performing a skill in a role play situation. This is only one kind of test, an integrative, subjective test (see Gorsuch, 1997). While it may be valid (very much like the actual situation in which a student would use clarification requests), it may not match objectives you would write, or your situation. Another person might write the objective this way: "the student will be able to supply the correct clarification requests What? Please speak slowly. What does that mean? I don't get it. Say again? Did you say _____? in five printed dialogs with 80% accuracy." In this case, an objectively scored, discrete point test would be more appropriate. It would also be appropriate in situations where the class is large, or where teachers/testers want item answers that are unambiguously correct or incorrect.

Third, write the test items (recall from the first article in this series [Gorsuch, 1997] that item is just a fancy testing term for test question). Plan on writing quite a few more items that you actually will use, because you're probably going to throw some of them away -- no one can write good test items the first time around, not even experienced, professional test item writers (J. D. Brown, personal communication, June, 1994). For concrete suggestions on the particulars of item writing, see Alderson, Clapham and Wall (1995, pp. 40-72), or Brown (1996, pp. 49-61). If you have a word processor or computer, you can keep the items on file.

Fourth, get item feedback from colleagues. Give your items to some colleagues to check. Ask them to make sure: (a) the items make sense; (b) there isn't more than one correct answer possible; (c) there aren't any spelling or grammatical errors; and (d) that the correct answer to one item isn't inadvertently being given to students in, say, another item. Ask your colleague for their opinion on whether your items are valid. If your test is a listening comprehension test, are your items really testing students on their listening comprehension? Or have you accidentally slipped a few grammar items in there? Finally, ask if your colleague thinks the students might be able to answer the questions before they even take the course. Generally, you want your items to be difficult but teachable.

Fifth, revise, organize, and proofread the test. After discussing the items with colleagues, discard items found to be hopeless and revise the other items where needed. Then organize the items into sub tests. Items written to test one of your objectives should generally make up one sub test. Finally, proofread the final version of the test. Brown (1996) recommends that sub test instructions are on the same page as the sub test items, and that when the test paper is printed on both sides, it be clearly marked so.

Sixth, at the beginning of your course, administer the test. This will be the pretest. With luck, the students' scores will be fairly low. Keep a record of the students' pretest scores. You will need them for two reasons: (a) for student diagnosis purposes (you'll be able to see what students already know and don't know, right at the beginning of a course) and (b) for future test revision, which will be mentioned briefly at the end of this paper. Students will perhaps be upset at their low scores on the pretest, but if you explain in simple terms that they haven't had the course yet, and that you'll give the test again at the end of the course and will show them objectively how much they have improved, most students will understand and appreciate what you're doing.

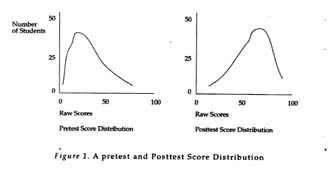

Seventh, at the end of your course, administer the test again. This is your post test. If you taught your objectives as you planned at the beginning of the year, and your test really does reflect the objectives, students should do much better on their post-tests (see Figure 1 below). It is very empowering for students to see this very concrete evidence of their learning. You can use the post-test scores to create students' test grades.

While some teachers make a cut point and simply pass those students with scores above that point, and fail those below, most students in formal educational institutions, such as high schools or colleges, expect A, B, C, or D grades on their tests. J. D. Brown suggests (personal communication, December, 1996) creating a number of cut points. Students getting scores above your "A cut point" will get As, while students getting scores above your "B cut point" will be Bs -- and so on (see Figure 2 below).

Finally, if you plan to use this test again for future courses, you will need to revise and improve the test using information from both the pretest and the post test. Tests need to be periodically reviewed and revised. While long term test development is beyond the scope of this paper, some remarks will be made about it at the end of this paper.

To recap, the process of developing sound classroom tests comprises the following:

- Formulate course goals and objectives

- Decide what type of test will fit your goals and objectives (objective vs. subjective)

- Write the test items

- Get item feedback from colleagues

- Revise, organize, and proofread the test

- Administer the test (pretest)

- Administer the test again (post-test)

- Revise and improve the test for future use

- Developing an Achievement Test for a Core English Curriculum

The test which will be described is part of a new core English curriculum for all first year students in a small liberal arts junior college/university in Saitama Prefecture, Japan. The testing program for the curriculum includes three tests: a general English proficiency test administered at the beginning and end of the year, a general proficiency vocabulary test, and a criterion-referenced classroom achievement test administered as a pretest at the beginning of the semester (April) and as a post test at the end of the semester (July). It is the creation of last of these tests, the classroom achievement test, that will be detailed below. The eight teachers assigned to teach this core English curriculum will be referred to below as the "whole committee."

The general proficiency test was administered just before the academic year began. The test was machine scored on-site, and the results were used to place students in one of three levels in the curriculum designated A, B, and C, with A being the highest level. There were five classes designated A level with about 125 students.

Three teachers assigned to teach the A level classes were also assigned to write and pilot the classroom achievement test for the A classes -- these teachers will be referred to as the "A test committee." The whole committee met once a week for 90 minutes to discuss curriculum issues, including the tests. Teachers were required to attend this weekly meeting and were paid the equivalent of an extra class to attend. Although the whole committee subdivided itself into the three levels A, B, and C, the whole committee discussed issues concerning all levels, and decisions were made by consensus.

Goals and objectives for the three levels were brain stormed and discussed until there was agreement (this paper will discuss only the A class). See Table 1.

Table 1: Overall purposes, goals, objectives of the A level classes

| Overall Purposes | Goals | Objectives |

|

To prepare students to understand and respond to extended discourse such as lectures, TV, and radio talks. To help students be able to make simple presentations. To help students be able to narrate in the past. |

The students will understand extended discourse, such as lectures and speeches. The students will be able to ask questions regarding lectures and speeches. The students will be able to read written materials of increasing difficulty for gathering information for personal and academic purposes. |

The students will be able to listen to and understand simple lectures. The students will be able to ask pertinent questions regarding lectures and speeches, the students will be able to make presentations such as a report in a seminar, and they will be able to narrate events or experiences in the past. The students will be able to understand simple academic writing, and an increasing number of newspaper and magazine articles. |

An objective, discrete-point test format was decided on for the level A classroom achievement test. By "objective" in this case we meant that items on the test could be graded unambiguously as "correct" or "incorrect." It was felt that an objective, discrete point test could provide high reliability (students would answer the test items consistently) and would be easy to grade (Remember, there were around 125 students enrolled in the A level classes.)

As the A test committee, our next decision was to have three subsections on the test, one for each of the objectives (see Table 1). To capture the first objective, "the students will be able to listen to and understand simple lectures," a short lecture on the topic of "How I learn" was recorded by a teacher not working on the test and 20 multiple choice questions were written. To capture the second objective, "the students will be able to ask pertinent questions regarding lectures and speeches . . ." 10 questions were written about the lecture described above, five of which would be appropriate in an after-lecture Q and A situation (e.g.,Can you explain the first point again, please?) and five of which would not be considered appropriate (e.g., Do you ride the train to school?). Students were asked to mark (0) for each question they felt were important for understanding the lecture, and mark (X) for each question they felt were not important for understanding the lecture. To capture the third objective, "students will be able to understand simple academic writing . . ." students were asked to read a short passage from a current text on learning styles (Nunan, 1988, p. 91) and answer seven multiple choice questions which were listed as items 19 through 25. The passage contained 174 words with a Flesch reading ease scale of 39 and a grade level of 15.

All test items were reviewed by the full committee of curriculum teachers with long and sometimes bitter debate. Some teachers with a literature background maintained that the reading passage was too difficult. Other teachers thought that particular items were worded badly. The group of three A level test writers/teachers went back and rewrote many items incorporating feedback made by the whole committee with 12 items for section one of the test, eight items for section two and six items for section three. The items were submitted for review once again, and again, long debate followed -- again the A level test writers/teachers revised the test and returned with a second set of revised sub tests of ten items, eight items, and seven items for a total of 25 items. By this time the spring semester was about to begin -- time ran out -- and the test was accepted.

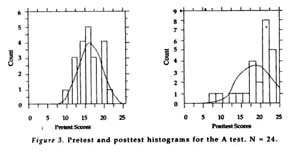

The A level classroom achievement test was administered during the first week in April as a pretest, and again in July as a post test. Histograms based on the pretest and post test scores of 25 students from the A-level class are shown in Figure 3.

The histograms in Figure 3 show the students' scores on the pretest and post test. On the left side of each histogram are numbers that indicate how many students received a particular score on the test. On the pretest for example, four students received a score of 20 points. There has been some overall improvement from the pretest in April to the post test in July. Notice how the distribution for the post test has moved to the right -- you can see that more students received higher scores on the test (13 students had scores of 20 to 24 points on the post test, whereas with the pretest, only five students scored above 20 points). Still, the situation is not ideal. From the pretest distribution, it appears that the students already knew some of the material that was to be taught in the course. Itユs also possible that the test wasn't very reliable. At it turned out in later analyses, this was the case.

The Need to Review and Revise Goals, Objectives, and Tests

From the very beginning, it had been the operating assumption of the curriculum committee that after each semester all goals, objectives, and tests would be reviewed, and revised when appropriate. Therefore, after the administration of the pretest and post test described above, the course goals and objectives were closely examined by the A test committee, reviewed by the whole committee, and accepted. The second objective (see Table 1), which actually contained three objectives, was revised and a new goal and objective was written.

It was also found that the test had to be revised. In Figure 3 above, students' total scores are depicted. What the histograms in Figure 3 do not show is how each item in the test functioned. By "functioned" we mean what percent of the students answered each test item correctly. Information on each item was crucial because we needed to know to what extent each item was functioning. A spreadsheet program was used to examine both the pretest and the post test item by item (see Griffee, 1995 for a detailed explanation of this process). We found that some items functioned better than others, perhaps because of the way they were written. For example, some test items were answered incorrectly by all students, on the pretest and the post test. But other items were always answered correctly, even on the pretest. We wanted a test with items which were answered incorrectly on the pretest and correctly on the post test. While further discussion on this issue is beyond the scope of this paper, see Alderson,Clapham,and Wall (1995) and Brown (1996) for explicit suggestions on how to review and revise tests, using qualitative and quantitative methods.

Note that the test writing and development process exemplified by the core English program described here did not precisely follow the eight step process prescribed above. Nevertheless, the teacher/testers in the program followed the general model, which includes the all important last step, reviewing and revising the test.

References

- Alderson, J. C., Clapham, C., & Wall, D. (1995). Language test construction and evaluation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

-

Brown, J. D. (1996). Testing in language programs. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

- Gorsuch, G. J. (1997). Test purposes. The Language Teacher, 21(1), 20-23.

-

Graves, K. (Ed.). (1996). Teachers as course developers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Griffee, D. T. (1995). Criterion-referenced test construction and evaluation. In J. D. Brown & S. O. Yamashita (Eds.) Language testing in Japan (pp. 20-28). Tokyo: The Japan Association for Language Testing.

-

Nunan, D. (1988). The learner-centred curriculum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The authors would like to thank the teachers and students of the core English curriculum at an unnamed school in Saitama Prefecture that provided a real life example of how goals, objectives, and tests are developed and implemented.